The Challenges of Our Time Are Not Technical but Social in Nature

How do we decide where we are going? And why?

I read a lot about new technologies. Technologies for health, the energy transition, the future of mobility, or mobile phones. And for many engineers, legal or societal issues are "non-problems." I used to see it that way myself. But when I look at the world, it is actually the opposite: Every technical challenge we currently face can be solved if we, as a society, decide to take it on together. The real problems, however, are not technical. They lie in deciding what matters most to us. Which challenges we want to solve.

Translated article. German original: Die Herausforderungen unserer Zeit sind nicht technischer, sondern sozialer Natur

This translation was started with an AI model to test its quality and then revised again and again over at least two hours to fix errors which distorted even the core message.

What is important to us

If health were truly important to us as a society, then there would be no antibiotic-resistant germs because neither doctors nor farmers would distribute antibiotics like candy. Instead, billions would be invested in research on how to keep animals in a way that they don’t get sick in the first place, and doctors would receive training from independent, publicly funded institutions, while drug development would be more socially financed rather than by companies that need to sell in the largest possible quantities at the highest possible price. The money is there; it is just used differently.

We see how much money is available in every war, where billions are burned without hesitation. For the cost of just four hours of the Iraq war, we can launch a research satellite into space1. NASA's entire budget is only 5% of the U.S. military budget. China now pays far more for the military than the U.S. pay for spaceflight.

Or, closer to home, we see it in the massive financing of smartphone development. As a society, we choose to invest enormous amounts in computing development—because most people constantly buy new phones, leading to software developed mainly for the latest devices rather than for all devices sold in the last ten years.

And smartphones instead of health is not the only example. If the energy transition were important to us, we would have stopped burning coal, oil, and gas ten years ago. We would have invested hundreds of billions in research and would have been much further ahead 10 years ago than we are today. We saw during the banking bailout that the needed money exists. If combating extremism and terrorism were important to us, then no child in the world would go hungry—also not in Germany or the U.S.. The money for that exists, too. It is just used differently.

But none of this happens. Because today's real problems are not technical but social in nature.

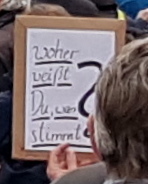

sign for Science

March, Stuttgart 2017

How do we decide as a society where we want to go together? How do we know what is true, and how do we know what is important? How do we decide what we ourselves consider to be reality? And whom do we believe and trust?

These are the truly difficult questions of our time—and they have been the important questions ever since humanity no longer had to fight for survival as a species every day.

Technology

That does not mean that technology is irrelevant. This is evident in advancements in agriculture and medicine. Thanks to plows, vaccinations, and antibiotics, fewer people were needed to secure a community’s basic needs, freeing up workforce for education and research. And when guns and long spears were developed, nations no longer needed a knight caste trained from childhood to protect themselves from neighbors. The invention of the printing press facilitated the spread of ideas outside church structures.

Technology shifts the boundaries of our decision-making. It changes how large certain groups must be to dominate societal discourse. If there are enough autonomous combat drones to control a country and a small group of people has control over them, then others in society can no longer make a difference, making their discourse irrelevant. The same applies when armed, self-proclaimed religious warriors force everyone to obey.

Technology can increase or decrease the number of people who must collaborate to control society. For example the internet initially expanded this number before shrinking it again due to the dominance over public perception and personal communication by a few corporations2.

And due to climate change, we may push ourselves as a species so far out of our comfort zone that technology becomes the real challenge again—so that we do not know whether we, as individuals, as a society, and as a species, can survive in the long run.

Society

However, the decision which technology we use and which we allow or limit—or develop only defensively—is a social decision. While our understanding of technology improves and the number of scientists in natural sciences continues to rise, the social sciences stagnate: disciplines like psychology, sociology, and political science that explore how we make decisions in groups and how we can make better decisions. Despite the fact that technology—through Facebook, YouTube, Mastodon, and extensive communication analysis—has opened gold mines for social sciences, they receive little support. And that is a problem.

And unfortunately, this, too, is social. As a society, we must recognize that the key to solving the major problems of our time lies in the social sciences. More precisely, in social sciences that serve society and the common good and everyone by helping to understand how people can make meaningful decisions in groups—also and especially when different interests are at odds. Sciences that search for (and communicate) ways to organize society such that more people can see which measures truly align with their interests and which other interests exist. How to make political structures act more in the interest of the people they represent. And how to assess the consequences of their collective decisions—to understand what freedoms they really have and which choices would have side effects they would consider worse than their immediate benefits.

Enlightenment

This means we need a next step of enlightenment: the path of human society out of self-imposed immaturity. If we all understand who and what influences our decisions, we can also decide for ourselves to whom we want to grant this power. And that will be uncomfortable because, just like during individual enlightenment, immaturity is pleasant as long as we blind ourselves to its consequences. But as in individual enlightenment, the gain from responsibility and self-determination is far greater than the inconvenience of having to acknowledge reality.

This step needs you—the one reading this text. Because while we can only take many of the important steps in a community, enlightenment always begins with individuals.

- Which sources of information do I trust?

- How do the things I focus my attention on change me?3

- Who do I want to work with?

- With whom do I discuss news? Do we question the sources?

- Where can I discuss news confidentially?

- With whom do I want to create change?

- With whom do I want to spend my free time?

- Which groups can bring forth a larger movement?

- How can we sustain it?4

- What do I want to change?

- What do I want to preserve?

- How does my elected representative inform me about what they have achieved with my vote?

- How do I ensure that those representing me learn what matters to me?

- To whom have I entrusted the task to champion my interests?

- What gives me the courage to take action?

And after the questions: Please pass this text on to those who might be interested, in a way and with a note that shows them you have truly considered it. This way, it contributes to societal (self-)enlightenment.

Link to share:

https://www.draketo.de/politik/challenges-technical-social

Call for a new step in enlightenment:

https://www.draketo.de/politik/challenges-technical-social#enlightenment

Footnotes:

The internet initially increased the number of people required to control society, because we could all publish (German article). Today, it is reducing that number, as it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish who is actually reliable—or even whether we are interacting with a real person or a paid propagandist.

How paying

attention to certain things changes us is described, for

example, by cycling journalist Kate Wagner in her report on how she was once invited to a Formula 1 race:

“I experienced firsthand the intended effect of allowing

riffraff like me, those who distinguish themselves by way of

words alone, to mingle with the giants of capitalism and their

cultural attachés.”

How can we sustain our communities despite opposition from those who seek to prevent group formation? How do we resist power concentration, surveillance, and fragmentation? (German article)